SAC Bases:

Wright Field, Patterson Field /

Wright-Patterson

AFB |

|

|

The history of Wright-Patterson AFB literally began with the origins

of manned, powered, controlled flight. Following their successful

proof-of-concept flights at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in December

1903, Wilbur and Orville Wright selected an 84-acre plot of land

near their home in Dayton, Ohio, to serve as their experimental

flying field, as they sought to transform their invention into a

practical flying machine. Here at the Huffman Prairie Flying Field

in 1904 and 1905 they developed the first practical airplane (the

1905 Flyer) and, as Orville noted, “really learned to fly.” Over

this prairie, now a part of Wright-Patterson AFB, the brothers

performed the first turn and circle in an airplane and solved the

final mysteries of flight. Here, too, they invented and used the

first successful aircraft catapult launcher. |

|

|

The brothers returned to the Huffman Prairie Flying Field

in 1910. This time the field served as home to the Wright Company School

of Aviation, the Wright’s flight exhibition company, and a test range

for their aircraft company. Among the graduates were Army Lieutenant

Henry “Hap” Arnold, who was sent to the school in 1911 to earn his

wings, and A. Roy Brown, the Canadian Ace who received the aerial credit

for downing Baron von Richthofen, the Red Baron. The Wright brothers

operations on the Huffman Prairie ended in 1916 when the aviation school

closed its doors. During these years, the Wrights had used the Huffman

Prairie as a research and development facility, flight test center,

logistics depot, and training field. These functions became precedents

for operations around the Huffman Prairie site for the rest of the

century. Even more important, the “can-do” spirit that Wilbur and

Orville brought to the flying field would inspire their heirs to push

aeronautical engineering to its technological limits.

|

World War I

When the United States declared war on Germany in 1917, the War

Department began a rapid expansion of its military facilities and

purchased McCook Field, Wilbur Wright Field, and the Fairfield Aviation

General Supply Depot. It was named McCook Field and opened on

December 4, 1917. This 254-acre leased complex was located just north of

downtown Dayton. It became a temporary home for the Airplane

Engineering Division of the U.S. Army Signal Corps until Langley Field

in Virginia could be completed, but by the end of World War I, 2,300

scientists, engineers, technicians, and support officers were working in

McCook’s 19 sections and 75 branches. In the postwar period, this force

would dwindle to an average of 50 officers and 1,100 to 1,500 civilians.

McCook Field’s achievements proved so substantial that in May 1919 all

experimental aircraft activities being handled at Langley Field were

transferred to McCook. The Air Service Engineering School at the

field evolved into the Air Force Institute of Technology. Among the

Engineering School’s first graduates in the Class of 1920 was Lieutenant

Edwin E. Aldrin who also served as the school’s operations officer and

whose son, Major Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, would walk on the moon 49 years

later.

|

|

|

|

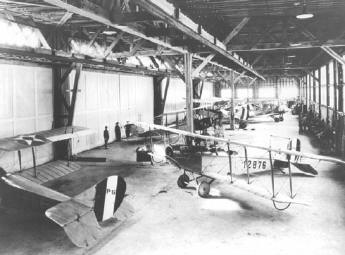

Curtiss JN-4D Jennys in McCook Field

main hangar, 1918.

|

Wilbur

Wright Field |

|

Construction of the

Fairfield Aviation General Supply Depot* began in the fall of 1917 on

forty acres of land immediately adjacent to Wilbur Wright Field that the

Army purchased from the Miami Conservancy District. The depot’s mission

was to provide logistics support to Wilbur Wright Field and the three

other Signal Corps Aviation Schools.

Rapid demobilization and restructuring followed the

conclusion of the Great War. On January 10, 1919, Wilbur Wright Field

merged administratively with the Air Service Armorer’s School and the

Fairfield Depot to form the Wilbur Wright Air Service Depot. Throughout

the years, the depot underwent numerous name and organization changes,

but was commonly referred to as the Fairfield Air Depot (FAD). In 1921

the depot became the home of the Property, Maintenance and Cost

Compilation Section, the earliest antecedent of the logistics component

of today’s Air Force Materiel Command.

|

Permanent Engineering Center

McCook Field had been built as a temporary experimental

wartime testing site and its shortcomings soon became evident. The

field’s short runways and obstructed approaches challenged pilots. Rapid

advances in aeronautical technology were producing larger, more powerful

aircraft that overwhelmed the field. It was becoming unsafe for

both aircrews and the local population. Its temporary buildings were

expensive to maintain and the field was hampered by the absence of a

railroad line. Finally, the rent for these inadequate facilities was

extremely high and landowners wanted to convert the land to more

profitable uses. These factors sent the War Department in search of a

new, permanent site for the Engineering Division.

When Dayton’s businessmen and citizens learned that

they might lose the engineering center, they seized the initiative. The

Engineering Division gave the community a stable and expanding economic

base. It was also a great source of pride for the city that considered

itself the birthplace of aviation. Furthermore, Dayton’s industries

directly benefited from the technology developed at McCook and the

skilled workforce that the Engineering Division attracted. Under the

leadership of the Patterson family (founders of the National Cash

Register Company), the city’s prominent citizens formed the Dayton Air

Service Committee to save the facility. The Committee soon reached an

agreement with the War Department to build a permanent engineering

facility in Dayton provided the land was donated to the federal

government. It then organized a 48-hour fundraising campaign that

garnered $425,000 of private money to buy the land and fund a monument

to the Wright brothers.

In 1924, the Dayton Air Service Committee purchased

4,520.47 acres of land northeast of Dayton and presented the deeds to

President Calvin Coolidge. The land donation included the previously

leased site of Wilbur Wright Field. The War Department combined this

gift with its adjacent site at the Fairfield Air Depot and redesignated

the entire acreage as Wright Field to honor both Wilbur and Orville

Wright.

|

|

|

|

McCook Field facilities being

dismantled for transfer to Wright Field |

Building 31, Wright Field Assembly

Hangar |

|

|

The

transfer of equipment and operations from McCook Field to Wright Field

begun in March 1927 was essentially completed by June, although the last

of the equipment was not moved until May 1929. The formal dedication of

Wright Field was held on October 12, 1927 with Orville Wright raising

the first flag over the new engineering center. The dedication

established three precedents. It was the first time that an Army

installation was named for two civilians who had never been in military

service. It was the first time an installation was named for a living

individual. And, in all likelihood, it was the first time that an

individual so honored by the military service was present at his own

memorialization.

As the nation’s foremost aeronautical engineering

center, Wright Field became involved in every aspect of aircraft design

and production. During the 1930s, the engineering trend at the field was

toward diversification, expansion, and modernization of aircraft design.

Engineers and scientists worked to improve aircraft structure and

aerodynamics. They developed a wide range of experimental and production

aircraft categorized by mission: attack, pursuit, transport,

bombardment, observation, photographic, training, and rotary wing. Each

innovation served as a stepping stone to the next. Thus, the Boeing B?9

and Martin B?10 bombers paved the way for the B?17 and became

progenitors of the B?29 as Wright Field engineers tried to develop a

true long-range bombardment aircraft. Wright Field was also instrumental

in marketing aircraft to foreign nations. The work performed in the

1930s would soon provide America with a decisive edge. The aircraft that

won World War II were either in development or production when the

conflict began.

|

Patterson Field

Although the entire installation had been named “Wright Field” in 1924,

there was considerable community support to formally recognize the

Patterson family’s leadership in keeping the Engineering Division in

Dayton. This recognition occurred on July 1, 1931 when the War

Department redesignated that portion of Wright Field east of Huffman Dam

as “Patterson Field.” The area encompassed the original Wilbur Wright

Field, the Fairfield Air Depot, and the Wright brothers’ flying field at

Huffman Prairie. Patterson Field specifically honored Lieutenant Frank

Stuart Patterson, a son and nephew of the founders of the National Cash

Register Company. Lieutenant Patterson was a test pilot who lost his

life in the crash of his DH?4 aircraft during a test flight at Wilbur

Wright Field on June 19, 1918. The two fields remained physically

separated until after World War II, but their missions continued to be

closely intertwined.

|

|

|

| Brick Quarters |

Wright Memorial |

|

|

Patterson

Field was a logistics center throughout the pre-war period. The

Fairfield Air Depot retained its title and operated as the major

organization on the installation. The depot had support responsibilities

in 28 states and serviced 28 of the Air Corps’ 50 stations in the United

States. In 1931 it had 15 officers and 550 civilians and generated a

monthly payroll of $67,000. Its headquarters moved from Building 1 (the

installation’s original depot structure) to the newly completed Building

11 in 1933. Several acres of Patterson Field were set aside in 1934 to

house a Transient Camp for temporary workers employed under

Depression-era programs. During 1934 and 1935, these men labored on a

number of projects such as the renovation of buildings and landscaping.

Young men residing in the Civilian Conservation Corps camp that was set

up on the field helped landscape the installation in 1935 and 1936.

The workers also contributed to the construction

of Wright-Patterson’s Brick Quarters. Built in an area described as “an

unsightly weed patch,” the 92 housing units were erected to house all

the officers assigned to Wright and Patterson Fields. Designers arranged

the $1,722,000 complex in the shape of a horseshoe with the Turtle Pond

centered along its main axis and the Officers’ Open Mess situated at the

crown of the curve. Large, private back yards enhanced the neighborhood

and created an atmosphere of informal tranquility in these junior

executive style homes. The jewel of the complex was Quarters 1, since

memorialized as “The Robins House” for its first occupant, Brigadier

General Augustine Warner Robins. It was the residence of the

installation’s senior officer.

As a depot, Patterson Field supported Air Corps

operations throughout the nation. It also played a key role in several

operations. In 1933, it hosted the Air Corps Anti-Aircraft Exercises and

the next year it modified and supported military aircraft assigned to

carry the U. S. Mail. When Lieutenant Colonel Henry “Hap” Arnold (a

former depot commander) initiated the long-distance Alaskan flight of

1934, Patterson Field prepared the aircraft and supported the operation.

The field was also the scene of the world’s first entirely automatic

landing which took place in 1937. New additions to the Patterson Field

community included the Air Corps Weather School in 1937 and the first

military Autogiro School in the United States. It opened in 1938.

Another landmark, the Wright Memorial, was dedicated on

August 19, 1940. This tribute to the Wright brothers was constructed by

the Dayton community on a 27-acre site owned by the Miami Conservancy

District. The Olmsted Brothers architectural firm designed the memorial

which sits atop a 100-foot bluff adjacent to Wright Field overlooking

the Huffman Prairie Flying Field. Funds raised by the Dayton Air Service

Committee in 1924 as part of its campaign to keep the Engineering

Division helped finance the monument. Six native American burial mounds

are also nestled about the memorial.

|

World War II

World War II profoundly altered both Wright and Patterson Fields. From a

combined population of 3,700 in 1939, the workforce at the two fields

would eventually peak at over 50,000. The workload shifted from a

40-hour week to round-the-clock operations. The faces of the two

installations also changed rapidly as massive construction programs

erected new work centers and housing complexes to accommodate wartime

operations. Existing facilities were modified and converted to new uses.

|

|

|

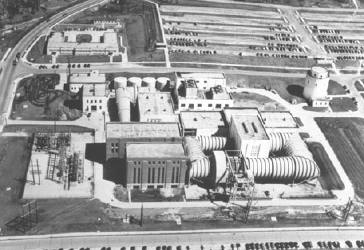

| Wind Tunnel Complex |

Air Service Command

Headquarters, Building 262 |

|

Numerous

laboratory structures joined the Wright Field complex. Among these were

the vertical wind tunnel (Building 27) for parachute testing and the

20-foot wind tunnel (the world’s largest). The huge Static Test Facility

(Building 65) was constructed to test the B?36 bomber. Engineers

designed and built an acoustical shell around the propeller test rigs

(Building 20A) so the constant droning would not disturb the sleep of

base personnel and the civilian community. Wright Field expanded in size

as well when the Hilltop area along National Road was acquired. This

land area became home to the Wright Field headquarters (Building 125), a

parade field, a barracks complex, and quarters for the prisoners of war

who were interned at the field.

Work at Wright Field centered on research,

development, and procurement, with emphasis on the latter. The race to

increase propulsion power and efficiency was the field’s most

significant R&D effort of the war. These efforts, for example,

eventually enabled heavy bombers to exceed 30,000 feet and the B-29 to

approach an altitude of 40,000 feet. The field’s engineers and

scientists conceived and put into production the airplanes responsible

for Allied victories.

|

Post War

Victory brought great celebration. It also gave Wright Field an

opportunity to educate the public on its achievements and the revolution

in aviation technology that World War II had spawned. Wright Field

hosted a two-day Army Air Forces Fair in October 1945 that attracted

500,000 people. The fair was so popular that base officials extended it

for a week. More than one million people from 26 foreign countries

observed displays of Army Air Forces operational and experimental

aircraft. The highlights of the event were exhibits of captured German

and Japanese aircraft, rockets, and equipment. In all, over $150 million

worth of equipment, much of it previously classified, was put on

display.

Victory also brought demobilization and a return to

“normal” operations. Procurement moved to the back seat as the

operational emphasis at Wright Field returned to research and

development, although the focus of the work shifted from

propeller-driven aircraft to jet propulsion. Wright Field also moved

away from developing, modifying, and improving individual items in favor

of a coordinated approach that emphasized new systems and models. In

late 1945 the Air Documents Research Center moved to Wright Field from

London. Working under T?2 Intelligence, a team of almost 500 people

catalogued, abstracted, indexed, and organized 55,000 captured German

documents representing the cream of Germany’s aeronautical research and

development. German aircraft and engines were also shipped to Wright

Field for analysis. Finally, Projects Overcast and Paperclip brought

prominent German scientists to the field where they contributed their

knowledge to the future of American aeronautical engineering.

When the war ended, Patterson Field hosted an

Army Air Forces Base Unit Separation Center that processed over 35,000

soldiers from the service. Peace also dramatically reduced the depot’s

supply and maintenance operations. In January 1946, depot operations

formally ended at Patterson Field when the Fairfield Air Depot was

officially inactivated and its functions transferred to Air Materiel

Areas.

|

Bases merged into Wright-Patterson AFB

As World War II was coming to an end, managers at both Wright

and Patterson Fields began to jointly plan and administer the two

fields. In 1945 they integrated the master plans for Wright and

Patterson Fields into a single document and increasingly administrated

the functions and services of the two fields as a single installation.

This practice was formalized in December 1945 with the establishment of

the Army Air Forces Technical Base, Dayton, Ohio, which consolidated the

two fields into an umbrella organization for administrative purposes.

The AAF Technical Base was redesignated on December 9, 1947 as the Air

Force Technical Base to reflect its status as part of the new,

independent United States Air Force. The final evolutionary step came

one month later. On January 13, 1948 Wright Field and Patterson Field

were officially merged into a single installation and redesignated

Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. To facilitate daily management,

Patterson Field became “Area C” and Skyway Park (located across Kauffman

and encompassing the area that is now Wright State University) became

“Area D” of the installation. Wright-Patterson AFB was assigned to

Air Materiel Command

|

The Cold War & Korea

Wright-Patterson Air Force Base became a

unified installation just as the Cold War began to heat up. The Berlin

Airlift, Korean War, and other Cold War activities directly impacted its

operations. The Berlin Blockade and Airlift began in June 1948 and

lasted until September 1949. The installation’s manpower soon rose from

a postwar low of 21,000 in 1947 to 25,000 in 1949. During this time, the

aircraft logistics support that made the airlift possible was directed

by Headquarters Air Materiel Command in Building 262. AMC managed the

transfer of the larger and faster C?54 transports to Germany and

maintained a pipeline of parts and supplies that kept the aircraft

flying. It also arranged for contract maintenance to handle the

overwhelming workload created by the operation.

When the Korean War broke out,

Wright-Patterson’s workload and labor force rapidly expanded to meet

wartime demands. Automation and decentralization became major trends at

Air Materiel Command. The rapid acceleration and expansion of aerospace

technology led to new, specialized research centers throughout the

country. Through the course of the 1950s, Wright-Patterson transferred its

large engine testing and ballistic missile development to these centers as

well as its electronic support systems, armament, and rocket engine work.

New tenant organizations added to the

flightline activity. The F-86Ds and F-104 Starfighters belonging to Air

Defense Command’s 97th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron (later redesignated

the 56th FIS) provided air defense for the industrial areas of the Miami

Valley from 1951 to 1960. The 58th Air Division also operated an air

defense control center for an eleven state area from 1955 to 1958.

|

Strategic Air Command

The Soviet Union launch of the

Sputnik space satellite made the Strategic Air Command aware that a

missile that put an satellite into orbit could also deliver a nuclear

bomb to its bases. B-52 bases had three squadrons of 15 planes each.

Each was converted into a strategic wing and dispersed to separate

bases.

Wright Patterson AFB acquired 465

acres on the northeast corner of the installation where it built the

West Ramp complex to house the SAC wing and its B-52 bombers and KC-135

tankers. The 42nd Bomb Squadron of from the 11th Bomb Wing became

the 4043rd Strategic Wing. It began operations at Wright Patterson

AFB on April 1, 1959, where it maintained six aircraft on ready alert.

It was also assigned the 922nd Air Refueling Squadron.

The 17th Bombardment (tactical) flew B-26s during

the Korean War. When it returned to the states in 1955, it began

flying B-66s. It was inactivated June 25, 1958. Redesignated

the 17th Bombardment Wing, Heavy, it was activated at Wright-Patterson

on November 15, 1962 and replaced the 4043rd Strategic Wing in February,

1963. It absorbed the 42nd Bomb Squadron and 922nd Air Refueling

Squadron. It trained to maintain proficiency in strategic bombing and

aerial refueling on a global basis. It furnished B-52s KC-135

aircraft and crews to SAC units in Vietnam from 1966 to 1975.

The 17th Bombardment Wing transferred to Beale

AFB, California, in 1975 thereby ending the strategic nuclear alert

mission at Wright-Patterson. |

The Vietnam Era

The Air Force opened the decade of the 1960’s with a

major restructuring that would govern operations at Wright-Patterson AFB

for the next thirty years. On April 1, 1961, the Air Force transferred

Air Materiel Command’s procurement and production functions for new

systems to the ARDC. It then redesignated AMC as the Air Force Logistics

Command (AFLC) and ARDC as the Air Force Systems Command (AFSC).

Routine business at Wright-Patterson soon gave way to

the growing requirements of the nation’s military operations in Vietnam.

Headquarters AFLC’s requirements for supporting the forces and bases in

the theater of war grew rapidly. By September 1964, AFLC was calling

upon the 2750th Air Base Wing for assistance. The wing immediately began

shipping materiel and providing support personnel to the combat theater.

It quickly became a prime procurer of loaders, revetments, and shelters.

In November 1965, the wing provided fifteen members for AFLC’s first Air

Force Prime BEEF (Base Engineering Emergency Force) mobility military

civil engineering force. Other base support over the years included

flight training, small-arms weapons training, vehicle operator training,

and laundry management courses.

On the Wright Field side of the installation, the

research laboratories and the Aeronautical Systems Division were busy

inventing and improving the systems used by warfighters. The

laboratories were developing jet fuels and lubricants for all services,

working on phased array radar and airborne lasers, exploring the use of

composite materials in structures, and pursuing stealth technology and

fly-by-wire technology.

Wright-Patterson AFB in 1960 had 100 tenants

representing 150 organizational units and boasted fixed capital assets

of over $208 million on base and $6 million off base. As in previous

conflicts, the base population jumped, this time from 25,000 to over

30,000 by 1964. It then declined before stabilizing between

25,000-26,000 for the duration of the war. Meanwhile, consolidation and

automation continued as trends in base support operations. |

1971-to Date

The end of the Vietnam War brought with it a period of

rapid transition and uncertainty within the defense establishment.

Mmany activities at Wright-Patterson AFB converted from government to

contract operations. Organizational changes occurred as the Air

Force moved away from its Vietnam-era structure toward one better suited

to the Cold War and the dynamic progress of technology.

Base flying operations in the post-Vietnam era

underwent dramatic changes. In 1975, the Air Force decided to retire

much of its aging fleet of administrative support aircraft and

reorganize the rest. The 2750th Air Base Wing transferred most of its

aircraft to the Military Aircraft Storage and Disposal Center in

Arizona.

The wave of historical interest spawned in the 1970s

was joined in the 1980s by an active concern with environmental

management. At Wright-Patterson, the environmental protection

initiatives included an investment of $37 million to modify and

modernize the base’s coal-fired heating plants. The base installed new

boilers and electrostatic precipitators to meet federal and state

environmental regulations and shut down three of its five heating

plants. Environmental managers also started surveying potentially

contaminated sites and developing remedial action plans to clean them

up. The World War II appearance of Wright-Patterson AFB continued to

fade as old facilities were either torn down or modernized and new ones

erected. Tenant units continued to arrive and depart the

installation. |

USAF Museum

Largest aircraft museum in the world. Over 300 aircraft

and missile on display. |

|

|

|